Using question lenses to identify conceptual themes

I first learned about question lenses through Buffy Hamilton, who wrote about using them to help her students focus their research topics. As Buffy wrote on her blog, this is “an activity shared [by] Heather Hersey, a school librarian in Seattle. Heather…adapted her version of the handout from An Educator’s Guide to Information Literacy: What Every High School Senior Needs to Know (Ann Marlow Riedling, 2009).”

I loved the idea of focusing research topics through lenses, and I was thinking about ways to use this strategy in other ways in the classroom. Emma, one of our US History teachers, is using conflict as a framework for exploring themes in American history. Right now, her class is focused on the run-up to the Civil War. Students have to conduct outside research over the weekends to supplement their work in class, and they read with a question in mind. This time, instead of assigning them a question, Emma wanted them to identify one of their own. So it was a great time to try using question lenses.

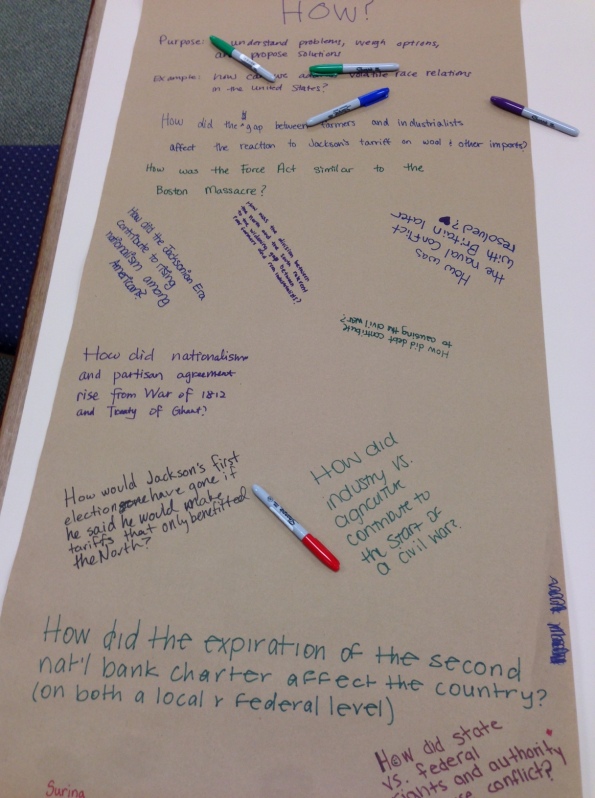

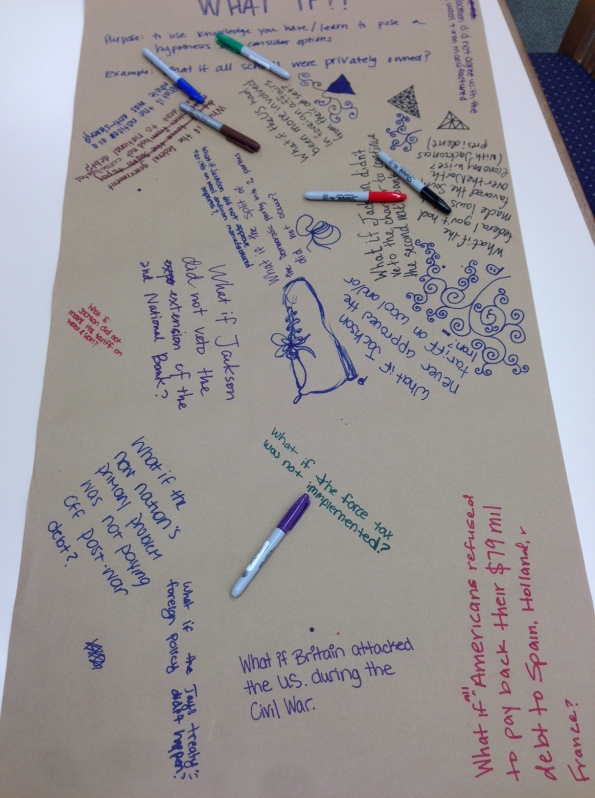

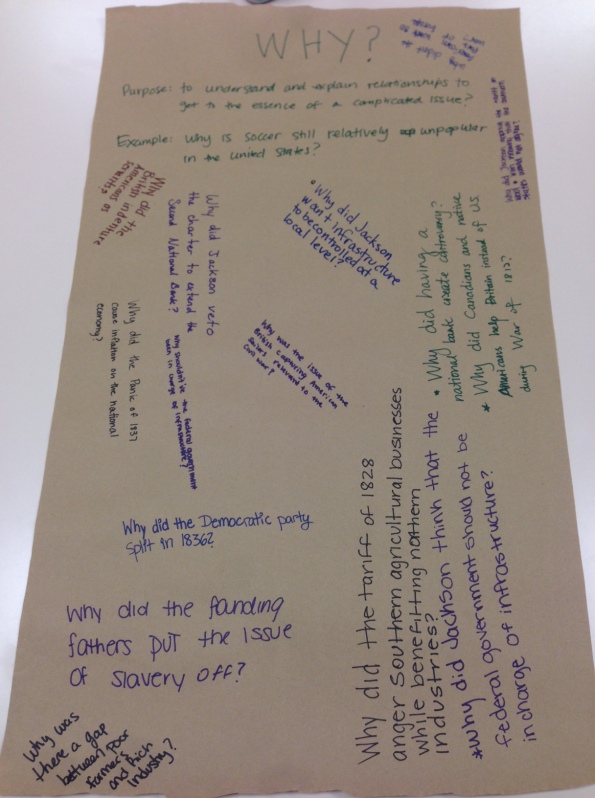

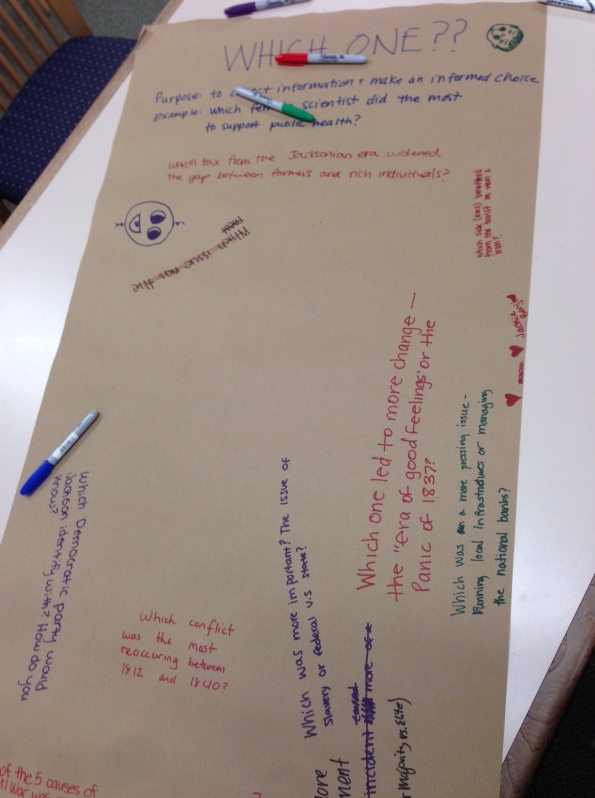

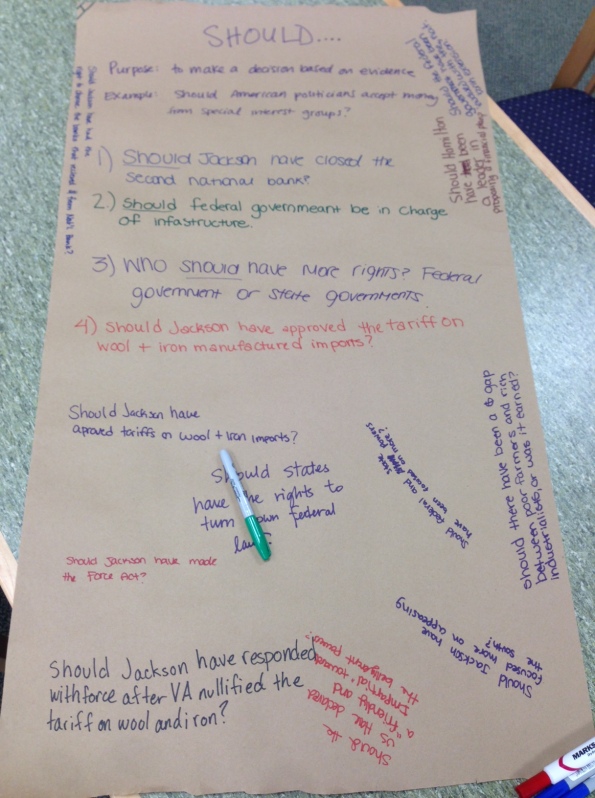

We began by introducing the concept of question lenses through examples. I grouped the students at five tables and wrote the lens and example on a big sheet of butcher paper. A member of each group read their lens and its example, and as a class, we discussed ways to find answers to that kind of question. This was tricky for some students, so it took some time for Emma and I to work with them on explaining the concepts we were introducing and helping them brainstorm the kind of information they’d have to seek out.

We instructed the students to identify a few questions at their table about their specific topic. We moved from table to table, helping them when they got stuck. The students had their class notes with them, using information there to help them find specific information to question. After a few minutes, the students got up from their table and moved to a new question. We didn’t structure this part of the lesson, allowing students to jump from table to table at their own pace until they had visited all five.

Once all the students had asked at least one question per table, they went back to their original seats, where as a group, they read over the questions and discussed them, working on identifying those questions that they thought were the “best” in terms of critical thinking and articulating conceptual themes.

Once all the students had asked at least one question per table, they went back to their original seats, where as a group, they read over the questions and discussed them, working on identifying those questions that they thought were the “best” in terms of critical thinking and articulating conceptual themes.

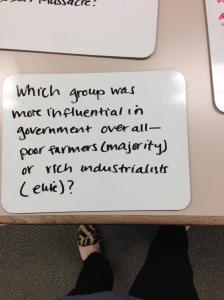

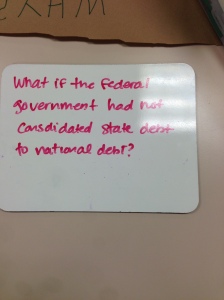

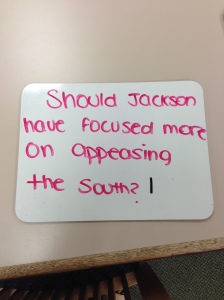

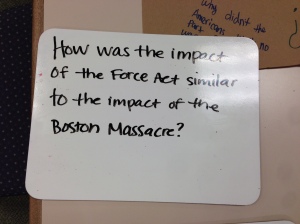

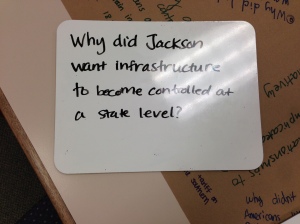

After several minutes of discussion, each group selected one question by consensus and wrote in on a small whiteboard at their table. A volunteer read the question to the class and explained why it had been selected. I then lined all the whiteboards up along a counter along the back of the room and the students voted on the question they wanted to use as a framework for their at-home research. (In the images below, I re-wrote four of the questions after they were erased by someone helping me clean up–and I misspelled “consolidated”!) The last question here is the one that “won.”

Reflection:

- As you can see from the photos, some lenses were trickier for the class than others. Emma and I were busy during this activity, sometimes pulling up a chair and spending several minutes helping students get started or find their way to a good question. Some questions were great, others less so. That’s fine–they don’t all have to be great, or even good. The students were sharp about identifying high-quality questions in the discussion part of the activity.

- The second class went better than the first (isn’t that always the way?). I wish I’d spent more time with the first class helping them understand what we were trying to do, as opposed to just blindly wading right in. Once that class got started, they were fine, but it took a while to get to that constructive point.

- Perhaps unsurprisingly, the first class selected a pretty straightforward question. Emma was unconcerned–she wanted them to dig more deeply in their outside research, to not just give a pat, one-line answer. The second class chose a question that would really require them to think critically and deeply about the subject.

- This activity took one class period (45 minutes), but it could have gone for two blocks. If we’d had the time, I would have had the students work together to brainstorm the kind of information they’d need to find to identify a hypothesis.

- Overall, I was pleased with the results of this activity, and I’ll try it again. I liked that it allowed for discussion and working in a group, as well as the individual work of writing.

(Also…has it really been a YEAR since I last updated my blog? Oops.)

3 Comments

Leave a CommentTrackbacks