Linda asked me to to share the process for this project, so here goes.

I’ve had great fun helping English class students choose books to either read independently or to read as a class. We’ve done plenty of book tastings and book talks, but this time we tried something different: the book pitch. I worked with our fantastic 6th grade English teacher, Justin (hi, Justin!), to create a one-day activity for his students to select their next class read. We decided to do a Book Pitch. Here’s how it worked:

- We started with a discussion about what we say when we want to get a friend to read a book we love. This led us to an exploration of plot (and spoilers!), characters, and genre. What might we say about a book to make someone else want to read it?

- Then students were put into small groups. A group at a time, they visited a table full of middle-grade and young YA titles that I had pre-selected for them. We had about 30 books for our 7 girls.

- Once back in their groups, the students each took a few minutes to read. They read the first few pages of the book, looked at any illustrations, and read the jacket/flap copy. Then they had to agree on which book they wanted to pitch.

- Some students switched to other groups so that they could be with those who agreed with their picks. So in once case, one member wanted to read historical fiction and the other two members didn’t. She traded places to be with another group who liked historical fiction. Before this happened, Justin and I were a little nervous about the small groups coming to consensus, but this was a great solution and an element of the project that I would build into it in the future.

- Once they’d determined their book, the students spent some time researching the book. They read reviews and synopses, looked up any awards it had one, and watched book/movie adaptation trailers.

- They then had about 15 minutes to build a quick Google Slides presentation with the goal of convincing the others in the class to vote for their book for class read. Here’s the handout Justin created to guide this process:

In your small groups you’ve considered a number of books. Now that you’ve decided upon one book that you think the class should read next,it’s time to come up with a ‘pitch’ to try and persuade your classmates to vote for it.

Important elements to consider for your pitch:

1) How are you going to present your ideas: Google slides? A pitch without slides? Handouts? Another way?

2) How much of the plot are you going to share? What appeals to you about this book and its plot? Will these things or other things appeal to your classmates?

3 ) Do you want to share a short excerpt of the book as a handout, or read a quotation from the book aloud?

4) Focus on putting together a short, focused and clear presentation that is convincing.

All of the students chose to use Google Slides, probably because it was easiest/fastest. Some read excerpts (and some were more compelling than others), some shared illustrations, and all of them described elements of the plot and either the positive reviews the book had received or awards it had won.

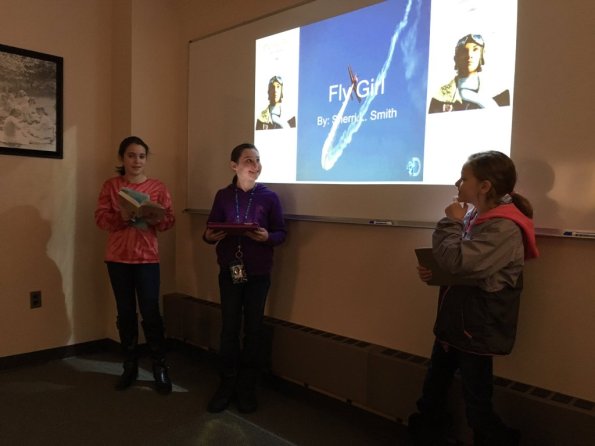

Group 1 chose to pitch Fly Girl by Sherri L. Smith. This was our historical-fiction-loving group.

Group 1 chose to pitch Fly Girl by Sherri L. Smith. This was our historical-fiction-loving group.

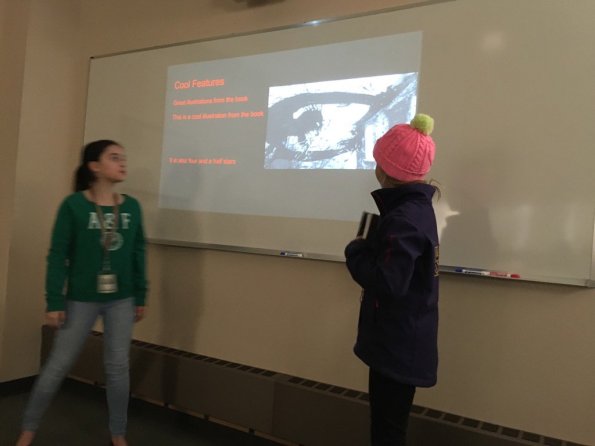

Group 2 immediately chose to pitch A Monster Calls by Patrick Ness. (They chose it over She is Not Invisible by Marcus Sedgewick. They were pulled in by the drawings.)

Group 2 immediately chose to pitch A Monster Calls by Patrick Ness. (They chose it over She is Not Invisible by Marcus Sedgewick. They were pulled in by the drawings.)

And Group 3 chose The Westing Game by Ellen Raskin.

And Group 3 chose The Westing Game by Ellen Raskin.

After the groups made their pitches, the class voted. There was a tie between The Westing Game and A Monster Calls (we had a visitor to our class, who helped with the activity and also voted), so then we did a tiebreaker vote and A Monster Calls won. This was interesting because that group only had two members, while the other groups had three. They must have done a good job convincing their classmates!

For next time…

I think Justin and I will find a better way to have the groups decide on a book to pitch, or find some way for students to self-identify with a book and form their own groups. This can be hard with such a small class. It’s also hard because everyone feels so attached to their own books. I’d like to build an activity that helps them consider options other than the books their group pitched. Perhaps we could make a score sheet or handout that would help. Or, if there was more time for the project, we could have all the students do a book talk.

This was a fun and relatively easy one-class activity. We planned it on a Thursday and introduced it the following morning. The students now feel invested in their next class read, and they have a taste of what’s to come in the story. Plus, the students whose books were not selected got to check them out and take them home. Everyone wins!

I’ll start by saying I did a few of the activities in this lesson on the fly. I can’t be the only one who does that, right? Plan a lesson and then make a quick mid-course correction?

When you primarily work with high schoolers, 6th grade can often require some quick thinking. Sixth graders are highly focused on a single idea for one minute and bouncing around from thought to thought the next. They can be great at following directions and also so absorbed at the task at hand that you have to physically move yourself into their line of vision to get their attention.

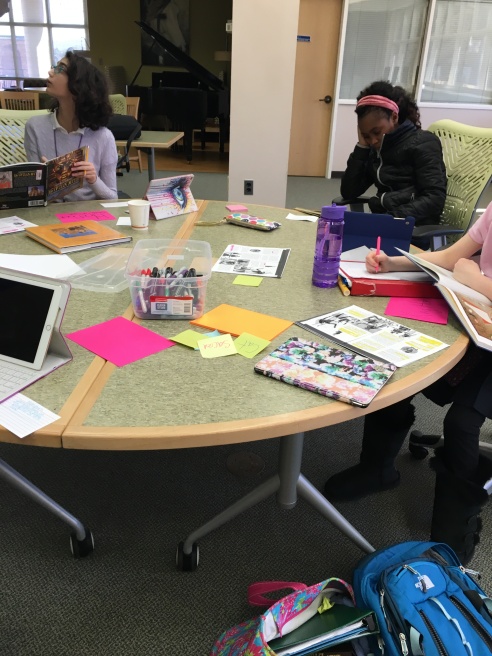

When our little class of 6th graders came into the library today for history class, they started out by asking me if britannica.com is a database. It was a great way to start the lesson and I love that they had that question. From there, we were off and running on a preliminary research lesson that served as the underpinning for their unit on Egyptian deities.

Step 1: Reading

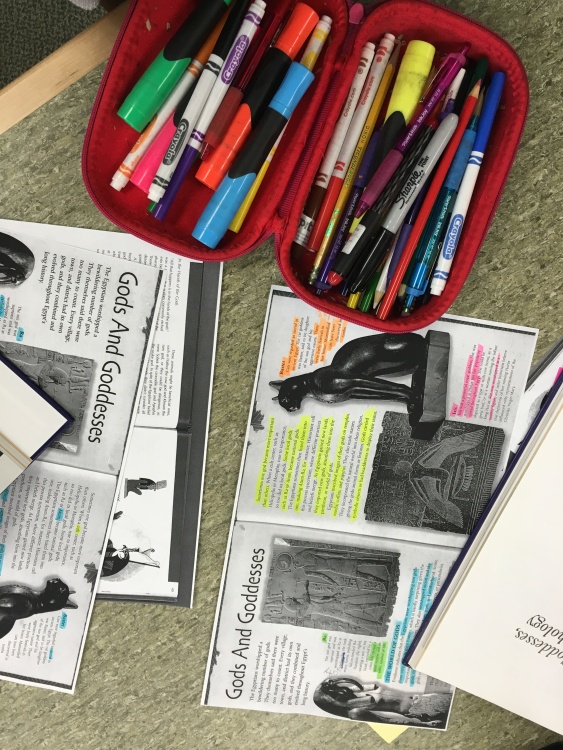

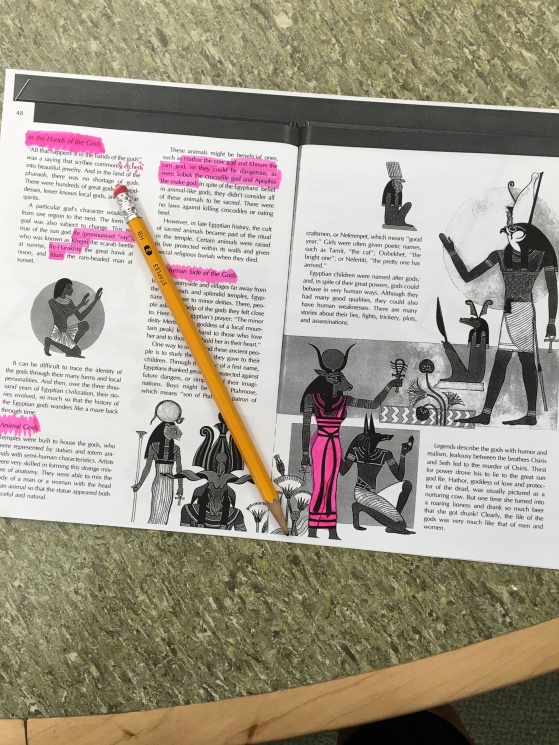

The girls are each researching an Egyptian god. They’re at the very beginning of their project and they have a benchmark on Thursday from their teacher, to have a certain number of notecards with sources and notes. So we started with two general readings on Egyptian gods, both photocopied from books.

I instructed the girls to read through their selections, using two different colors of highlighter. One to highlight keywords, and one to highlight words they didn’t understand. We had a brief discussion about keywords and what that means. They could also use a pen to write in the margins of the pages. They read silently for about 10 minutes.

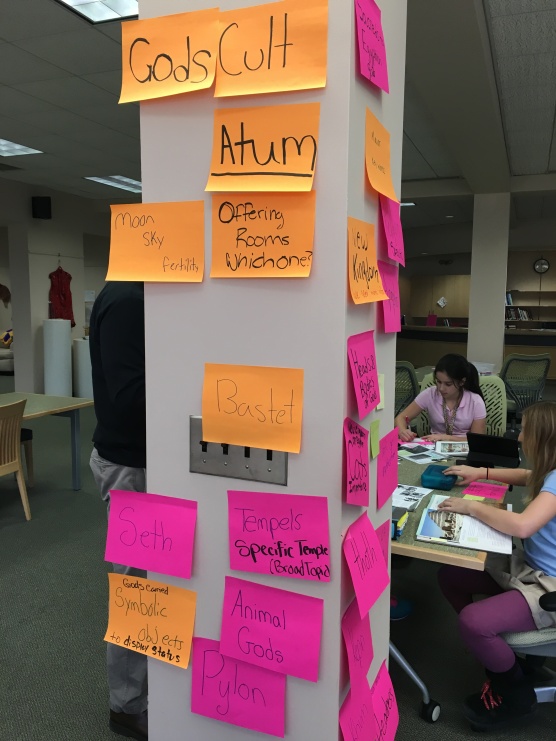

Step 2: Identifying keywords

Next, we had the girls go back through their readings and write down any keywords they thought were important on sticky notes–one sticky per keyword. I labeled one side of a column “Major Keywords.” The girls then put ALL their sticky notes up on the column–there were maybe 50 in all. We took a moment to survey them and then I asked for the students to identify any notes that were duplicated, grab them all, and rewrite the keyword on a giant sticky note. This took about five minutes. They were quickly able to identify which words were most important because they were physically represented on a larger sticky note. We looked at the remaining words and tried to determine what to do with them. Were they words that were less useful to us? Did they need to be clarified or expanded upon?

We also looked at the big stickies to see which terms were going to be harder to search. “Religion,” for example. Or “temple.” The students quickly understood that these terms were too general, and I asked volunteers to jot down what they needed to do to “fix” the term. Some girls investigated keywords that they thought might be related–two different names for one god, for example. Others added descriptors to narrow down the keyword. Others simply wrote down that a keyword was too broad or that “we need more info.”

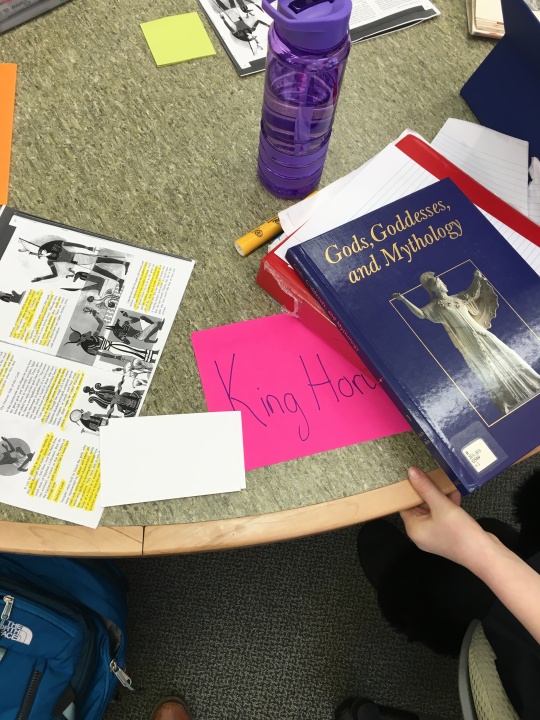

Step 3: Research

Once we were satisfied with our collection of words, I asked the students to each grab a sticky note and take it back to their seat. I had a cart of books for them to do their research in, and we had a brief discussion about what to do with these keywords. They got it right away–look in the index. For the rest of the block, the girls explored the books, taking notes on their notecards.

Step 4 (but we ran out of time): Group share

If we had had time, I would have had the students share one or two things that they learned in their research. I also would have had them reflect on the keyword activity. We got a bit sidetracked by our database/Britannica discussion at the beginning, and the keyword sort took longer than I anticipated–but it was the best part of the lesson, in my opinion.

Takeaways

With students this age, helping them understand the context of their research is critical. They were able to make connections between terms and identify strong keywords vs. weak keywords. It would be interesting to have them physically draw lines between the words, or categorize them. But in a single block, what we were able to accomplish was helping them toward the understanding that bid ideas can be represented by single words or phrases, and that using them is the most efficient way to search for information.

My son was born in June 2013. Not coincidentally, my last major blog posts and my last conference appearances happened in 2013. Since then, I’ve stopped writing for outside publications, posted to this blog only sporadically, and have stopped presenting nearly altogether.

When I Google myself (*cough*), I find lots of interesting things that seem as though they happened a very long time ago. Conrad’s arrival was a bit of a turning point for me. I wanted to be home more. I reduced my work hours for a year and stopped doing anything except work and hang out with my family.

But the other day in class, a history teacher colleague who I’ve been co-teaching with said something to the girls about creating their presentations. Their parents were visiting classes for family weekend, and he said “ask your parents for help. They probably know a lot more about presenting than Ms. Ludwig or me.”

I didn’t say anything. First of all, he could have been right. There may have been parents in the room who have presented loads of times. It could even be some of their occupations. And I haven’t presented in a long time now.

But still…something bothered me. Not my colleague himself. How would he know I used to do a lot of presenting? The thing that bothered me was that I was pretty decent at presenting at one point, and I miss it. I liked it. I liked speaking in front of a group, I liked sharing the things that have worked for me, and I liked connecting with people at conferences.

The sad thing is that I’ve missed all the deadlines for submitting proposals this year. Womp womp. But that’s OK. It will give me time to think about what I want to do. How I can ease myself back into this whole scene. I’d like to start writing again, and start sharing. The last time I presented, it was this fall. I was on an informal roundtable panel and I did a less-than-stellar job. I’m out of practice.

But I can get back into practice. I can start up again. So I’m writing this here, to keep myself accountable. That’s it for now. But hopefully not for too long.

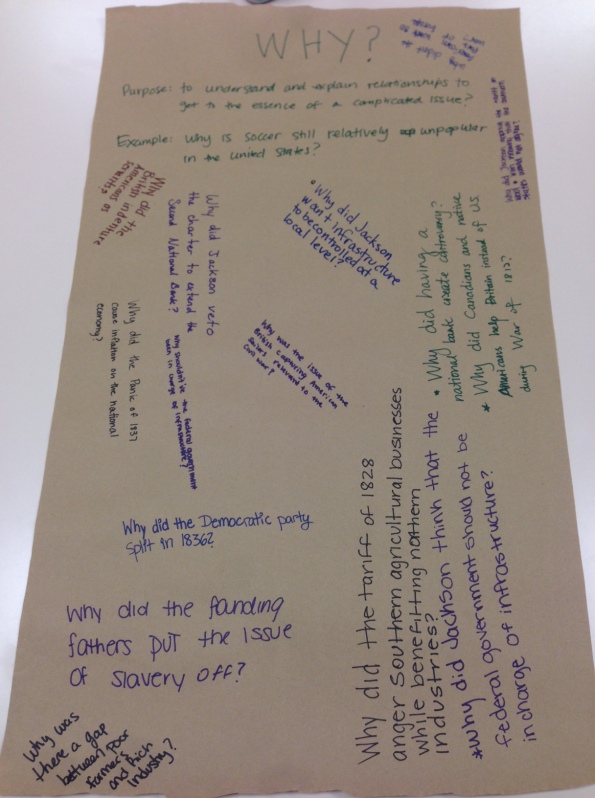

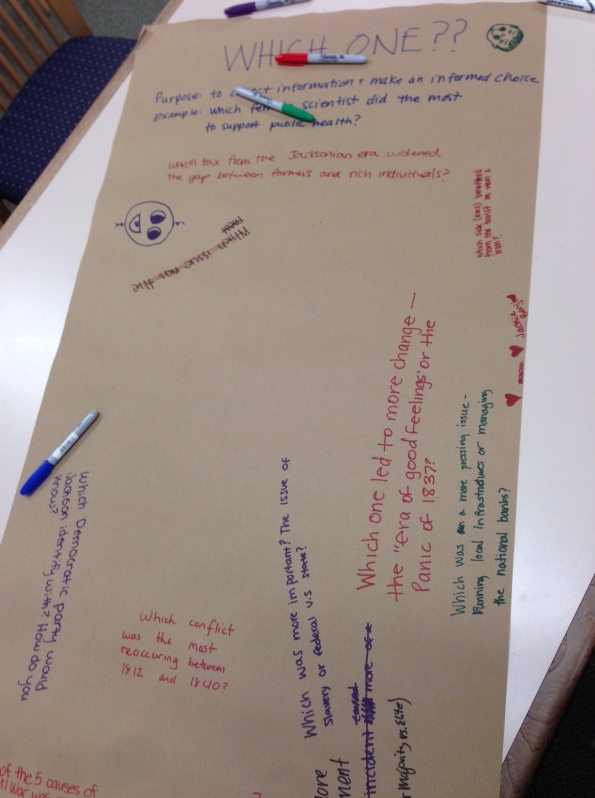

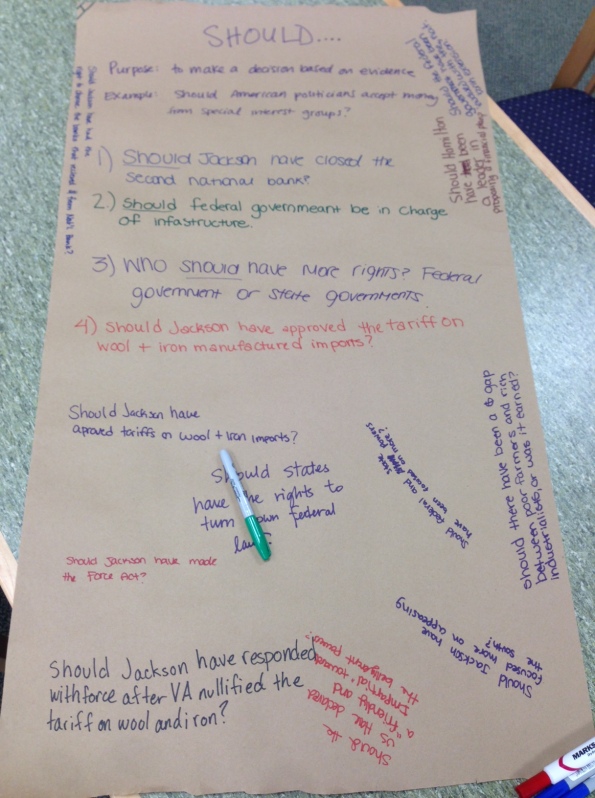

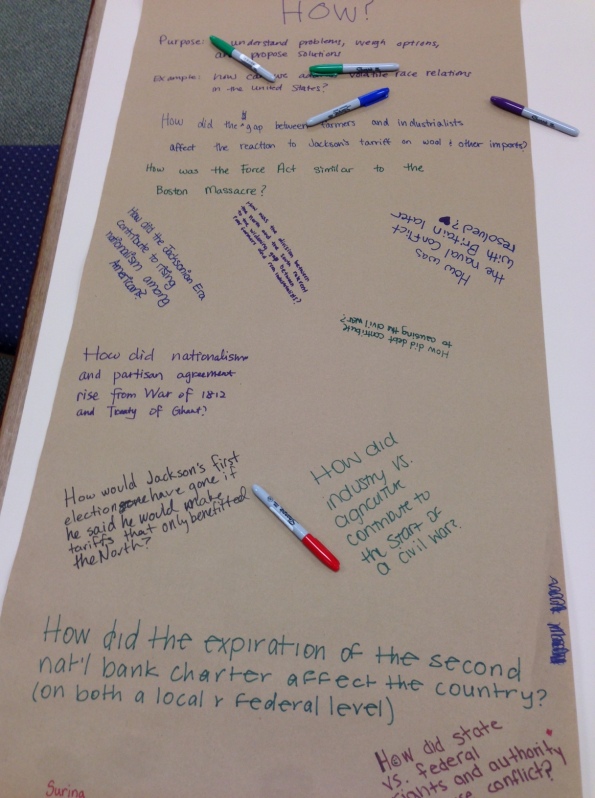

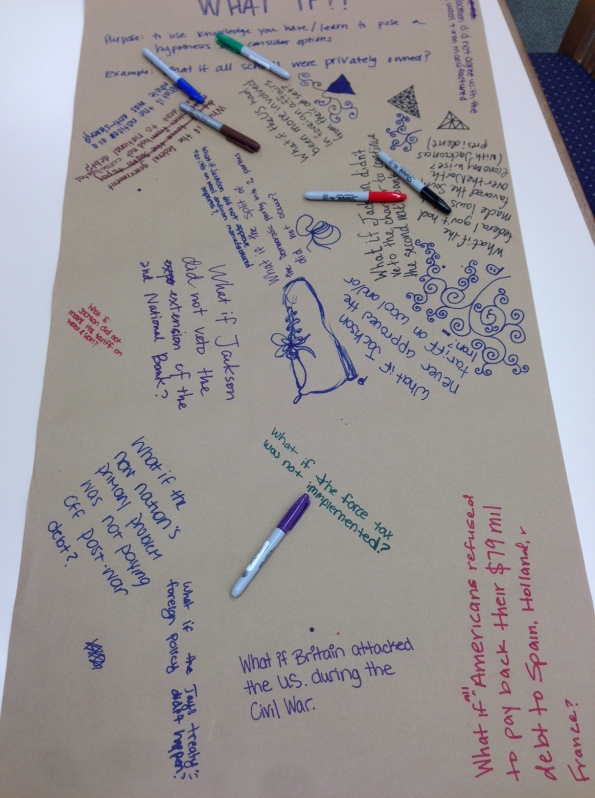

I first learned about question lenses through Buffy Hamilton, who wrote about using them to help her students focus their research topics. As Buffy wrote on her blog, this is “an activity shared [by] Heather Hersey, a school librarian in Seattle. Heather…adapted her version of the handout from An Educator’s Guide to Information Literacy: What Every High School Senior Needs to Know (Ann Marlow Riedling, 2009).”

I loved the idea of focusing research topics through lenses, and I was thinking about ways to use this strategy in other ways in the classroom. Emma, one of our US History teachers, is using conflict as a framework for exploring themes in American history. Right now, her class is focused on the run-up to the Civil War. Students have to conduct outside research over the weekends to supplement their work in class, and they read with a question in mind. This time, instead of assigning them a question, Emma wanted them to identify one of their own. So it was a great time to try using question lenses.

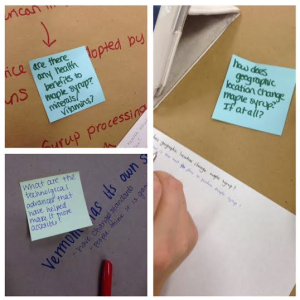

We began by introducing the concept of question lenses through examples. I grouped the students at five tables and wrote the lens and example on a big sheet of butcher paper. A member of each group read their lens and its example, and as a class, we discussed ways to find answers to that kind of question. This was tricky for some students, so it took some time for Emma and I to work with them on explaining the concepts we were introducing and helping them brainstorm the kind of information they’d have to seek out.

We instructed the students to identify a few questions at their table about their specific topic. We moved from table to table, helping them when they got stuck. The students had their class notes with them, using information there to help them find specific information to question. After a few minutes, the students got up from their table and moved to a new question. We didn’t structure this part of the lesson, allowing students to jump from table to table at their own pace until they had visited all five.

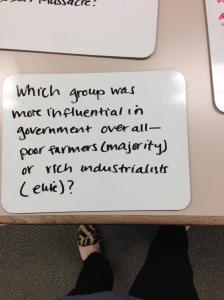

Once all the students had asked at least one question per table, they went back to their original seats, where as a group, they read over the questions and discussed them, working on identifying those questions that they thought were the “best” in terms of critical thinking and articulating conceptual themes.

Once all the students had asked at least one question per table, they went back to their original seats, where as a group, they read over the questions and discussed them, working on identifying those questions that they thought were the “best” in terms of critical thinking and articulating conceptual themes.

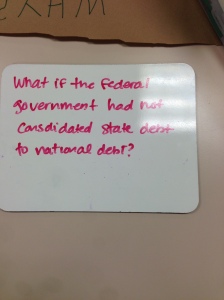

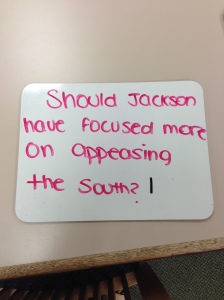

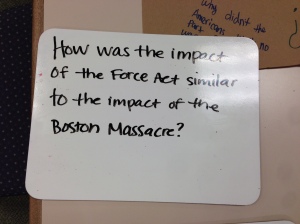

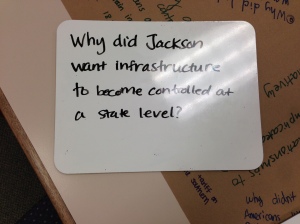

After several minutes of discussion, each group selected one question by consensus and wrote in on a small whiteboard at their table. A volunteer read the question to the class and explained why it had been selected. I then lined all the whiteboards up along a counter along the back of the room and the students voted on the question they wanted to use as a framework for their at-home research. (In the images below, I re-wrote four of the questions after they were erased by someone helping me clean up–and I misspelled “consolidated”!) The last question here is the one that “won.”

Reflection:

- As you can see from the photos, some lenses were trickier for the class than others. Emma and I were busy during this activity, sometimes pulling up a chair and spending several minutes helping students get started or find their way to a good question. Some questions were great, others less so. That’s fine–they don’t all have to be great, or even good. The students were sharp about identifying high-quality questions in the discussion part of the activity.

- The second class went better than the first (isn’t that always the way?). I wish I’d spent more time with the first class helping them understand what we were trying to do, as opposed to just blindly wading right in. Once that class got started, they were fine, but it took a while to get to that constructive point.

- Perhaps unsurprisingly, the first class selected a pretty straightforward question. Emma was unconcerned–she wanted them to dig more deeply in their outside research, to not just give a pat, one-line answer. The second class chose a question that would really require them to think critically and deeply about the subject.

- This activity took one class period (45 minutes), but it could have gone for two blocks. If we’d had the time, I would have had the students work together to brainstorm the kind of information they’d need to find to identify a hypothesis.

- Overall, I was pleased with the results of this activity, and I’ll try it again. I liked that it allowed for discussion and working in a group, as well as the individual work of writing.

(Also…has it really been a YEAR since I last updated my blog? Oops.)

I was recently inspired by Buffy Hamilton’s series of posts about Write Arounds, an activity I’d never heard of that sounded like a concrete way for me to partner with some of our English faculty. What began as a fun experiment bloomed into a bit of a breakthrough for me.

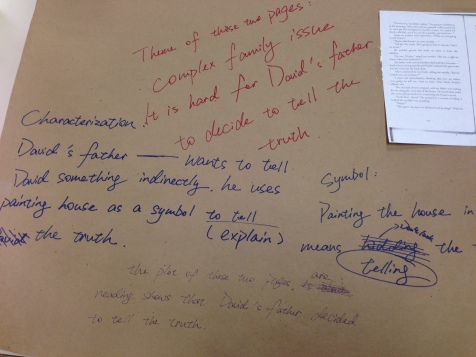

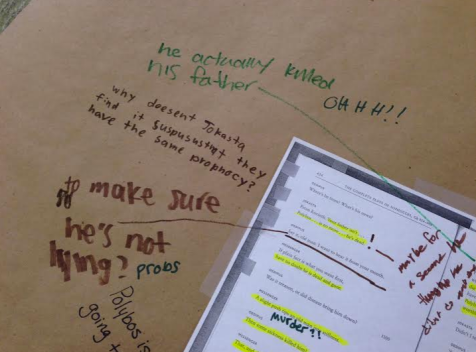

Write Arounds are a way of collaboratively reading, annotating, and questioning texts. Students sit at tables covered with butcher paper and read, as a group, a passage from a text they’re investigating. They can work together or alone, and can ask questions, take notes, highlight, draw pictures, etc. Their only limit is the size of the paper.

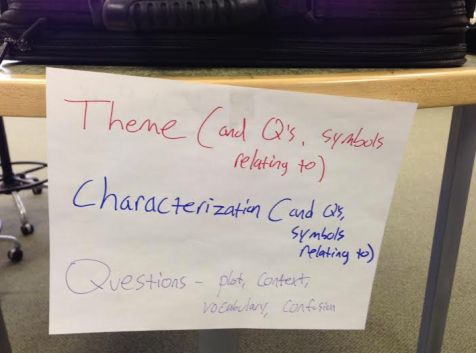

I tried Write Arounds with an English teacher in both his 9th grade English class–in both the Catcher in the Rye and Oedipus units–and with his ESL class, on the text they were reading (Montana 1948). In all cases, the students seemed to enjoy and benefit from the activity. I especially enjoyed watching the students in Scott’s ESL class. In his other two classes, we left the activity fairly open-ended, having all the girls start in pairs or teams of three at one table and then moving around the space to read and respond to each other’s work as well as to the new passages. In his ESL class, Scott had the students color-code their annotations, focusing on theme, characterization, and questions. This guidance allowed the girls to read closely and identify details in the text that were connected. It also allowed Scott to identify their level of understanding of the text, as well as directly answer questions they had.

Within Scott’s English 9 class, Catcher in the Rye was “easier” to work with. The girls were done reading the book and had spent ample time discussing it in class. They were ready to go. That said, Scott told me that the activity allowed some girls, who might feel less comfortable speaking up in class, to express themselves. He was also able to notice gaps in the students’ understanding of the text, things that might not have come up in discussion. When we worked with Oedipus, the students were not done reading and had not spent as much time talking in class. Therefore, it was a slower start and a bit more frustrating for the girls. Once they got going, Scott was able to watch them form their initial thoughts about the text–information he could then use to guide discussion.

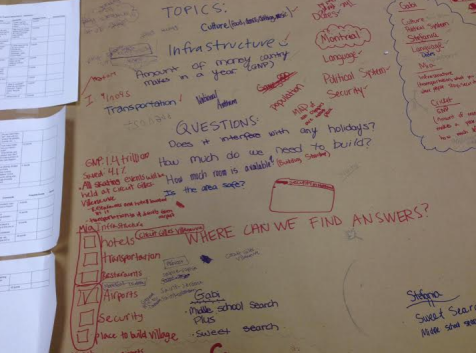

Last week, I worked with our sixth and seventh grade on a cross-curricular project. The students were competing in their own Olympic games (pairs figure skating in socks, etc.) and then writing a bid to have the next winter Olympics hosted in their assigned country: South Korea, Russia, Norway, and Canada. The girls were in teams of 4-6 and had an application to fill out as well as a presentation to make to the “IOC,” made up of administrators.

To help the girls get organized, I had them sit in teams around our big library tables. I taped the rubric and presentation requirements onto the paper and handed them Sharpies. Each paper had three things written on it: TOPICS, QUESTIONS, and WHERE CAN I FIND ANSWERS? I had the students read through the project requirements and identify major themes in the information they needed to find. They then started writing down specific questions that they needed to find answers to. After this, I introduced a research guide with various resources and gave them time to explore. They then needed to think about where they could find information for their topics and questions. Using the paper and the markers, they were able to draw physical connections between topics, jot down ideas, and assign themselves tasks. As time went on, the papers grew beyond these parameters, turning into giant notebooks full of information, drawings, to-do lists, and notes.

This was a fairly unfocused use of the paper on my part, but I loved that they were using it to record information. The students have saved their paper from one class to the next, stashing it in my office and then bringing it out again every time they come into the library. Essentially, it’s become the repository for all of their ideas.

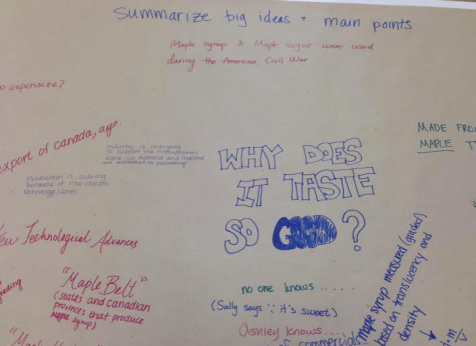

I was able to refine this with our AP Chemistry class today. In a long block (80 minutes), the students divided into three groups with specific tasks: summarize big ideas, take notes on specific content, and find connections (“why is this important?”). The topic? Maple syrup. They can choose any topic they like, as long as it’s related to maple syrup. For 20 minutes the students read through the Wikipedia article on maple syrup and browsed the Google News feed on the topic. As they read, they jotted down notes that connected to the theme of their table.

Next, the students moved around to other tables so that they could find connections between their own notes and the notes of others. They talked to each other, commenting on how they’d discovered the same information or elaborating on each other’s ideas. They also wrote down their thoughts on the other tables. Throughout the process, the AP Chem teacher and I circulated among the tables, asking questions and helping the students stretch their ideas.

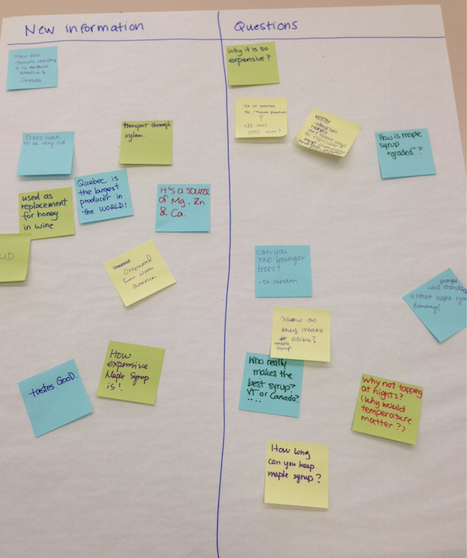

After this mingling, I had the students go up to an easel with two columns written on it: New Information and Questions. They wrote out a handful of ideas and questions on sticky notes and stuck them on the board, and then took time to examine the board and think about the topics that appealed to them the most.

Finally, I told them to take one sticky note off the board to use as the jumping-off point for their research.

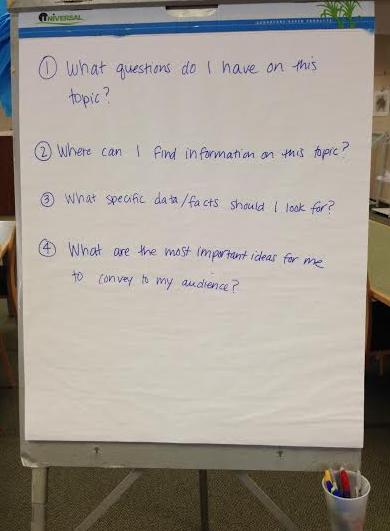

I handed out paper and had them start writing, using the following questions as a guide:

Of course, because they’re just starting, they will not be able to answer all of these questions right away. But because they had already spent an hour reading, talking, and making connections, they were ready to immediately begin to dive into the research process. Many of them developed question lists that were ten lines long…and that’s just the beginning.

By the time the class was over, the girls knew a ton about maple syrup…perhaps more than if they’d just spent 80 minutes reading and taking notes. They were able to add their own insight and information to the many cross-conversations that were taking place among each other, their teacher, and me. In addition, as with all of the other exercises I’ve written about, their teacher was able to watch the process of them learning and sharing, as well as to ask questions that helped guide them along the process. And the students ended the class with a topic that genuinely interested them as well as successful inroads into the research process.

The last thing I’ll say is that I find it fairly remarkable that something as simple as butcher paper has had such a significant impact on my instruction and the way that I think about learning and research. What I’ve learned over the past couple of weeks is that it’s about thinking, not about mimicry. Walking students step-by-step through the process of using a database, for example, is not nearly as valuable as helping them think and question.

Now that I am at the Ethel Walker School, which has a 1:1 iPad program, it’s time for me to suck it up and develop an ebook plan for the library.

I’ve been putting this off. I’m totally overwhelmed by ebooks and hate that it’s such a pain in the butt to explore all of my options. When you want to start collecting print materials, there are only a couple of places to go. Ebooks are another story. And it’s been surprisingly tricky for me to find information online about what other libraries are doing, especially libraries where all students have an ereader. So I thought I’d start chronicling what I’ve learned so far, just in case there are any other librarians in the same boat.

It seems to me that there are two major models for ebook delivery systems.

The first is paying for a database of ebooks. For a flat fee (anywhere from $1800 to $3150 for my school, with our enrollment of about 250 students), you get access to a large number of ebooks–some vendors offer upwards of 115,000 books.

The second model is one user, one book. You purchase a copy of an ebook just as you would a print book. For multiple copies, you buy multiple ebooks. These books range in price, but are sometimes much more expensive than print. Other times, there are circulation limits on the books. Students can check out a copy of a book, which means it’s unavailable to anyone else, and return it when they’re done. Vendors that offer this model charge a hosting fee of some kind–Baker & Taylor’s Axis360 is $250/year, while Overdrive’s, again for a school of our size, is $1000. They both require you to spend a certain amount on books as well–in our case, $1000.

So which model will work better for my library?

Remember, we are an iPad school, so in my research, I needed to make sure that ebooks were easily accessible via iPad. I know this is unique to my school and is often not a challenge faced by other schools, especially those whose students do not have access to ereaders or mobile devices. In those cases, reading on the computer is important–but not in my case.

Today I’m going to share what I’ve learned about the one checkout per book model, and focus on Axis360 and Overdrive. I have contacted 3M for more information about their cloud library, but I haven’t heard back yet and it doesn’t look like they really work with schools (yet). If I hear back and get more information, I’ll share it here.

Overdrive

Pros

- Overdrive has excellent customer service; they’ve been in the game a long time. I spent about an hour on the phone with one of their sales reps, talking about different options and features.

- In terms of mobile functionality, Overdrive appears to offer a robust and seamless experience. Students can search the library’s ebook holdings right from the Overdrive app, and books sync across devices.

- Overdrive offers a million-book catalog. Of those million books, they estimate that 350,000 are suitable for K-12 libraries. I have not received a publisher list for them, but they work with the major trade, academic, and school publishers, meaning that nearly anything that is available in ebook format is available through Overdrive.

Cons

- The industry leader, Overdrive’s platform is expensive, though I was actually pleasantly surprised at the price point. I’d put off exploring Overdrive because I’d assumed it would be prohibitively expensive, but the platform, at $1000 a year, is comparable to other systems. You are obligated to purchase $1000 worth of ebooks upon signing a contract, and will probably spend more, given the pricing model.

- You can integrate Overdrive’s records into your catalog, but they do not offer MARC records or book records for free. They do offer the raw metadata for each item…and I have no idea what I’d do with that.

- Overdrive offers patron-driven acquisition, which would come in handy given the collection development challenges of ebook collections (more on that in another post…)

- I’m frustrated that they do not allow you to truly demo the product or the acquisitions module, meaning that I just have to assume the process of checking out and reading a book is as easy as I hope.

Axis360 (Baker & Taylor)

Pros

- At $250/year, with a $1000 obligation, Axis360 is more affordable than Overdrive.

- The Magic Wall is B&T’s online platform for finding ebooks. It’s cover-heavy and attractive, and any materials you acquire will be displayed there.

- Ordering ebooks would be fairly a fairly seamless process, since we purchase print materials through B&T. Currently, those ebooks would need to be ordered through Title Source 3 while print is ordered through School Selection, though the rep did tell me there are plans to merge the two soon.

- MARC records are available to integrate the ebook collection into the catalog

- Students can also access the library’s holdings right from the Axis360 app.

Cons

- B&T provides access to 500,000 titles, which is obviously far less than Overdrive.

- It seems as though B&T is a bit less sure of their product than Overdrive–no disrespect to my sales rep intended. They are not as aware of some of the features and functionality, including some important stuff like catalog integration and use on mobile devices.

- From what I’ve read, some libraries have passed on Axis360 because of its more limited catalog. Would this be a real issue for us, though? I did some test searches to see if there were any differences in popular YA titles in both catalogs.

Overdrive: yes

Axis360: yes

Overdrive: yes

Axis360: yes

Overdrive: in audio only (so no)

Axis360: only available to public libraries (so no)

When I did some keyword searches for topics that high school students often research, I found:

Civil Rights Movement

Overdrive: 27 items

Axis360: 7 items

Roman Architecture

Overdrive: 0 items

Axis360: 2 items

John F. Kennedy

Overdrive: not sure? A search for “john f kennedy” gave zero results, and “john f. kennedy” led to 5 titles, none of which were related.

Axis360: 65 items

Climate Change

Overdrive: 68 items

Axis360: 77 items

Obviously, this is a really small sample. But on cursory glance, it does not appear that there is a huge difference in the results that a user might get back from these two platforms.

Do you use either Overdrive or Axis360 in your school? Would you like to share your feelings on them? Please do!

Stay tuned for a post about ebook databases…

A note on collection development: I will definitely write another post later on about how to collect ebooks. Or rather, on my ideas and the ideas of others, since I haven’t started collecting them yet and I’m still not sure how to approach the issue. If you have any thoughts on the matter, please feel free to comment here or get in touch on Twitter!